Brains & coding¶

Optional

This section is optional - it’s about the neuroscience of writing code. Feel free to skip to the next section if it doesn’t speak to you.

What makes coding uniquely difficult? Coding is hard on your memory. This book’s theme is that writing good research code is about freeing your memory. Neuroscientists distinguish different subtypes of memory, and coding strongly depends on two subtypes:

Working memory

Long-term memory

Let’s look at how these two types of memory are involved during programming.

Working memory¶

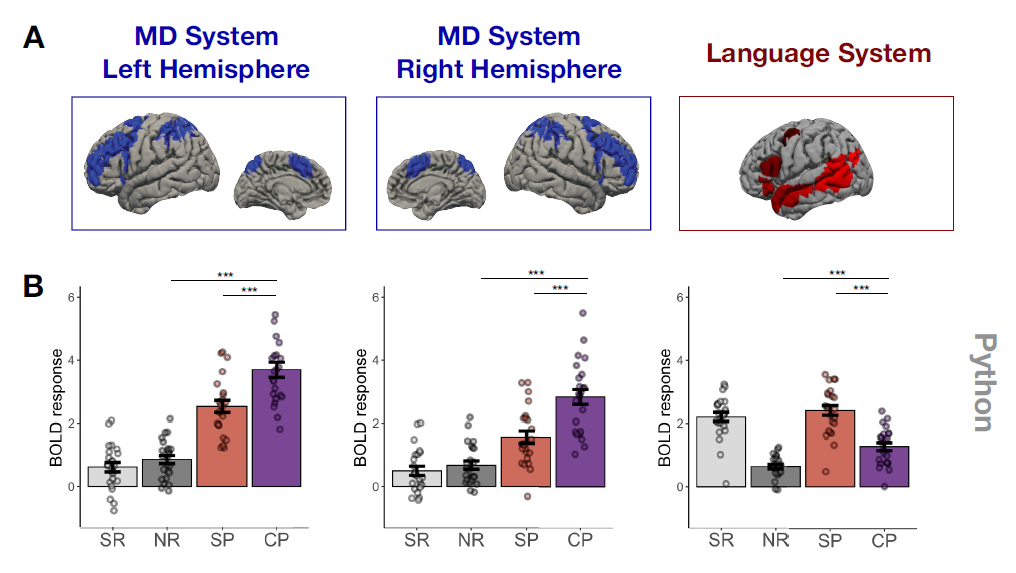

What do you think coding looks like in the brain? The term programming language makes it seem that reading code is like reading natural language. Neuroscientists have looked at what circuits are engaged when people read code. Ivanova and colleagues at MIT measured brain activity while people read Python in the scanner. They found that activations didn’t overlap much with conventional language and speech areas.

Fig. 2 Code problems (CP; purple bars) created activations with higher overlap with the multiple demand system (left and center) than with the language system (right) compared with other tasks like sentence problems (SP), sentence reading (SR) or non-word reading (NR). From Ivanova et al. (2020), used under a CC-BY 4.0 license.¶

Instead, they found high overlap with the multiple-demand system - a network of areas typically recruited during math, logic and problem solving. The multiple-demand system is also involved in working memory, a type of memory that can hold information for a short amount of time. You may have heard that people can only hold approximately 7 items in working memory - for instance, the digits of a phone number. This idea was popularized by the Harvard psychologist George Miller in the 1950’s. While there’s debate about the exact number of items we can remember in the short term, neuroscientists generally agree that our working memory capacity is very limited.

Programming involves juggling in your mind many different pieces of information: the definition of the function you want to write, the name of variables you defined, the boundary conditions of the for loop you’re writing, etc. If you have too many details to juggle, eventually you will forget about one detail, and you will have to slowly reconstruct that detail from context. Do that enough times, and you will completely cease to make progress. Your working memory is very precious indeed.

Saving our working memory¶

One of our strongest weapons against overloading our working memory is convention. Conventions mean that you don’t have to remember details in your working memory - you can rely on your long-term memory instead. For example, let’s say you want to call a helper function that splits a url into its constituent parts. You might instinctively know that the function to call is split_url and not splitUrl or splitURL or URLSplitterFactory().do. That’s because Python has a convention that says that you separate words in a variable name with underscores (snake case). If you abide by the convention, you’ve just saved yourself a working memory slot. To be clear, it’s a completely arbitrary convention: JavaScript uses a different convention (camel case) and it works fine.

We’ll see many more examples of organizing code such that it saves our working memory:

Writing small functions

Writing functions with low number of side effects

Writing decoupled functions

Following the Python style guide to the letter

Using an auto-formatter

Your working memory is precious, save it!

Long-term memory¶

What is this?

—You, squinting at code you wrote a year ago

Research code in particular is challenging on long-term memory. This is because:

The project’s endpoint might be unclear

Correct can be hard to define

There can be lots of exploration and dead ends before you produce a unit of research

Sometimes, manual steps are involved requiring human judgement

You have to remember all the dead ends for the code to even make sense

Has this ever happened to you?

You work on a project for many months, and you submit a paper. You receive reviews months later requiring revisions. You sit down to code and it takes you several days to figure out how to run a supplementary analysis that ended up taking only a few lines of code.

While the scientific method, as traditionally taught, is fairly linear, real lab work often involves a high nonlinear process of discovery.

Fig. 3 Generating a research paper can be a messy process.¶

Future you will have forgotten 90% of that process. Code that sticks to convention, is tidy and well-documented will be far easier to use in the future than clever, obtuse code. Boring code is good code!

Discussion¶

Simple is better than complicated. Complicated is better than complex.

—The Zen of Python

We’ve seen that coding - especially research code - is difficult along two axes:

working memory

long-term memory

We’ve discussed some of our overall strategies to deal with these limitations, namely:

using convention

keeping code tidy

documenting our code

Let’s see how you can implement these strategies in practice. Let’s jump in!